Opera Singer Lucy Schaufer Discusses her Experience of Performing Nude

Have you ever had one of those dreams where you’re just going about your business, only you realize that you’re naked? It’s supposed to be one of those universal dream scenarios, and is often rooted in deep anxiety about exposing ourselves, physically or otherwise.

And it’s sort of a funny thing, because we humans are really the only animals on earth that feel the need to cover up. Clothing was probably invented out of necessity to protect ourselves from the cold or from the sun, but now in modern society, most of us only feel comfortable disrobing in the most intimate of situations, or in a place secluded from the opposite sex.

Then again, in an age where a great deal of value is placed on achieving a certain physical ideal, we are bombarded with images of extraordinarily beautiful (often impossibly so–Link NSFW) naked or nearly naked bodies. They are mostly women’s bodies, but men’s too. In the interest of realistically portraying certain scenarios in drama, it’s not too unusual for performers to be asked to disrobe.

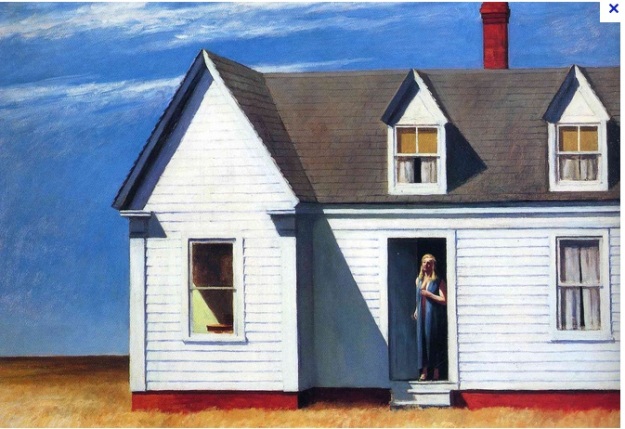

As a performer myself, one who might like to sing Strauss’s Salome one day, I wondered what it must be like to appear nude, on stage, in front of an actual audience, an audience of both women and men. I’ve written before about how annoying the talk of body issues has become in Operaland, but when it comes to singing in your birthday suit, it feels like a whole other thing. I read this lovely essay by actress Louise Brealey about the time she did a bit of naked acting in a play called Trojan Women, but I wanted an opera singer’s perspective. Mezzo-soprano Lucy Schaufer was very kind to share with me her experience of appearing nude twice(!) in the 1997 world premier of Hopper’s Wife at Long Beach Opera.

Lucy Schaufer as Ava in Hopper’s Wife. Photo by Keith Polakoff.

The opera explores the relationship of “high art” and “low art.” In it, Schaufer sang the role of Ava, fashioned after Hollywood Golden Age actress Ava Gardner, who models for an artist, Hopper, in the opera. “As it was in the context of posing for a painting, it felt substantiated.” Schaufer told me, “The character of Hopper appeals to Ava’s inner beauty, saying she has ‘roses inside her’ and speaks of her ‘bloom’ – she buys it hook, line and sinker.”

In another scene, Schaufer sang an aria which describes performing sexual favors in order to get ahead in Hollywood, from a bath tub and, in her words, “Ended my aria standing in the bath tub, starkers with bubbles dripping off my nipples!” That moment, according to a reviewer from the Orange County Register, “deserves a place in the operatic hall of fame.”

Now, when an opera singer prepares a new role, there’s a lot of work to be done on music, language, character development, etc., but for this role, Schaufer had a bit more to think about:

“I swam a bit, not much, and mostly worried about getting pimples on my back! Vanity, vanity, vanity. Also, how to handle or not to handle pubic hair in this situation. Set in the 1940s, well, a girl wouldn’t exactly wax it down to a Brazilian, would she? Therefore, how au naturel does one go? What is “comfortable” as far as how to protect your bits from wiggling in the wind when you’re naked, standing in 3 inch heels on a steeply raked stage. Turn up stage and you’re gonna be winking at the audience. I don’t mean to be crude but anatomy is anatomy.”

Having a fit, and well-groomed body is one thing, but in a society where we’ve been trained to cover our bodies pretty much from birth, there can be another hurdle to get over. “I had a whole row of family out there watching this show,” said Schaufer, “My parents, my aunts, uncles, cousins, nephews, nieces – and it’s a strict Catholic family! So shame was a personal issue I needed to conquer.”

But Schaufer found that her sense of duty to the production overrode that shame. “I didn’t want to be a sissy or a problem. Get on with it and do it. Courage!”

And with that, Schaufer took on the issue of getting herself used to it, and getting the rest of the cast and crew used to working with a naked woman.

“In rehearsal I selected the prettiest matching bra and panty set I had. These were special and that’s what I went down to every time. Then I bared all in the stage and orchestras. Final 3 or 4 rehearsals. First of all, in order to help the crew know how warm the bath had to be so I didn’t catch a chill, and then for the orchestra to get used to the fact that I was naked so they weren’t distracted. You’d think it wouldn’t be a big deal but it’s like a car crash: you can’t help but look. Same for my colleagues. It is only a 3-hander but still, Ava has a whole conversation with Mrs. Hopper while in the tub and at one point I decided to flash her my crotch (covered in bubbles, of course) but she needed an opportunity to know what that was like so it didn’t throw her. The more you do it, the more integrated the performance and the reaction belongs to the character, not the actor.”

Now, it seems like whenever you have live theater with nudity, the nudity itself can become the headline (and it is now occurring to me that this blog entry might be part of the problem). Schaufer didn’t necessarily find that was the case with Hopper’s Wife, but one review of the production began by cautioning potentially sensitive opera-goers about the show’s nudity, pornography and…tobacco smoke? Ok, whatever, but Schaufer did mention her frustration with the media’s obsession with nudity and sex, “I want the choice of being nude on stage or in film to be a question of the story telling, so I wish the media/PR people would get their collective heads out of their sometimes small-minded arses and stop sensationalising the beauty of the human body in order to drum up ticket sales.”

I asked Schaufer to touch on how performing in the buff might be different for a woman for a man,and she pointed out that there is a bit of a gender gap. “We women have been objectified for so long that it’s not so much of a ‘big deal’ – we don’t see men’s penises on stage very often.” She referenced the 2012 movie The Sessions, in which Helen Hunt plays a sex therapist who works with a man paralyzed by polio, played by John Hawkes: “look at Helen Hunt’s performance in The Sessions – she’s full frontal. Not so much John Hawkes, because that would have tipped it from an R rating to an X, I bet,” she suggested, “Again – not equal footing in the eyes of ‘censors’ or the law. Infuriating and it adds layers of emotional baggage and garbage which doesn’t belong.”

Throughout the discussion, Schaufer seems to be of the opinion that nudity is a tool that can and should serve art and story telling, and perhaps we should all just be adults about it. ” We have no issue or giggle fest when we contemplate a nude in an art gallery. We observe our common humanity. So grow up and allow us to embrace all we are, wrinkles, lumps, bumps and boobs.”

She also noted that every performer confronted with disrobing on stage will surely have his or her own reservations about it, “full frontal for both men and women is personal decision. Respect and dignity for all, please,” before going on to explain how she felt about her decision:

“If I am totally honest and withhold nothing from you: I was scared that someone might think I wasn’t pretty, that I wasn’t attractive. Now, I’m not sure how much of that was me or Ava – probably both, but in the end, it is Ava’s story because that moment of “release” is all she has to hold on to in the years that follow. Now, I want to be perfectly clear that I, me, Lucy didn’t want to be desired sexually when I was standing there naked. I wanted to be beautiful. I didn’t want to be judged. So yes, scared, nervous, but I’m damn proud I over came any worries, delivered what was asked of me and accepted the challenge I had set myself when agreeing to sing the role. I had said YES: I stepped through a barrier, a personal barrier which led to a sense of freedom of mind and body.”

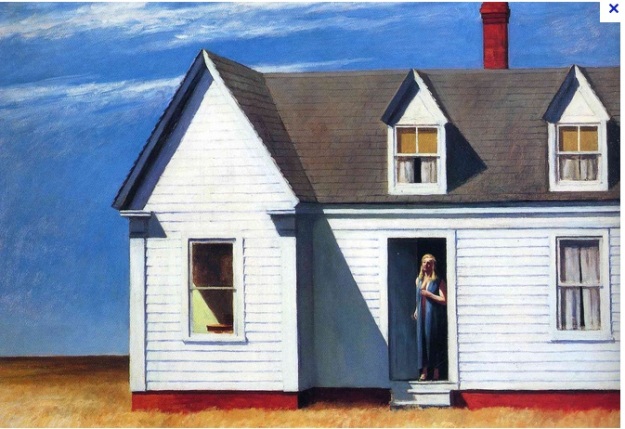

Edward Hopper’s “High Noon”

Be sure to visit http://lucyschaufer.com/ for all the latest from Lucy!